An intimate elegy for Ziad Al Rahbani: from Rahbani heritage and mythic village to Beirut’s raw vernacular, he shattered the Fus’ha–dialect divide, turned satire into national self-reflection, and shaped a generation—including the author’s path toward Aralects. His death feels like Lebanon losing its inner voice.

Tonight feels super personal. A hollow silence looms all over, the kind that comes after the last, devastating line of a joke, the one that contains so much truth you forget to laugh. Ziad Al Rahbani, the Lebanese composer of our national soundtrack of irony, disillusionment, and unyielding humanity, has died at 69. And with him, a certain voice, ours, has gone quiet.

This news really hits home for me because Ziad's impact wasn't just a blip; it profoundly shaped my path since I was 18. I used to totally brush off Arabic, even neglecting my education in it, until I somehow stumbled into Ziad's world. That encounter totally rerouted my life for the past ten years, pushing me to tackle my hang-ups about my Arabic—which came from my Lebanese French-speaking upbringing. His music drew me into his world, deeply resonating with me as it articulated my thoughts precisely when I most sought to define myself.

Some intellectuals emerge as singular forces, people like Noam Chomsky or Larry David, more music figures than I could count, whose profound influence and unparalleled contributions defy easy comparison. Such figures appear but once in a lifetime, shaping discourse and challenging conventional wisdom in ways that leave an indelible mark on their respective fields and on society at large. Ziad Al Rahbani was a national phenomenon. To lose Ziad is to feel a shift in our lexicon. His passing feels like a silencing of the city’s most honest, cynical, and ultimately most loving internal monologue.

It's no surprise that the generation most impacted by Lebanon's civil war now reveres Ziad, quoting his songs and plays at every opportunity. It's equally unsurprising that the spokesman for the Israeli army penned a deeply heartfelt message mourning his passing. He so conveniently chose the figure who commands the greatest popular consensus, aiming to gain sympathy from a populace profoundly affected by Israel's military aggressions in the region. The situation is so absurd, I'd be fascinated to hear Ziad's response if he were still alive, being one of Israel’s staunchest opponents in the country. I can think of no other individual today who could have such an impact on Lebanon's deeply fragmented population.

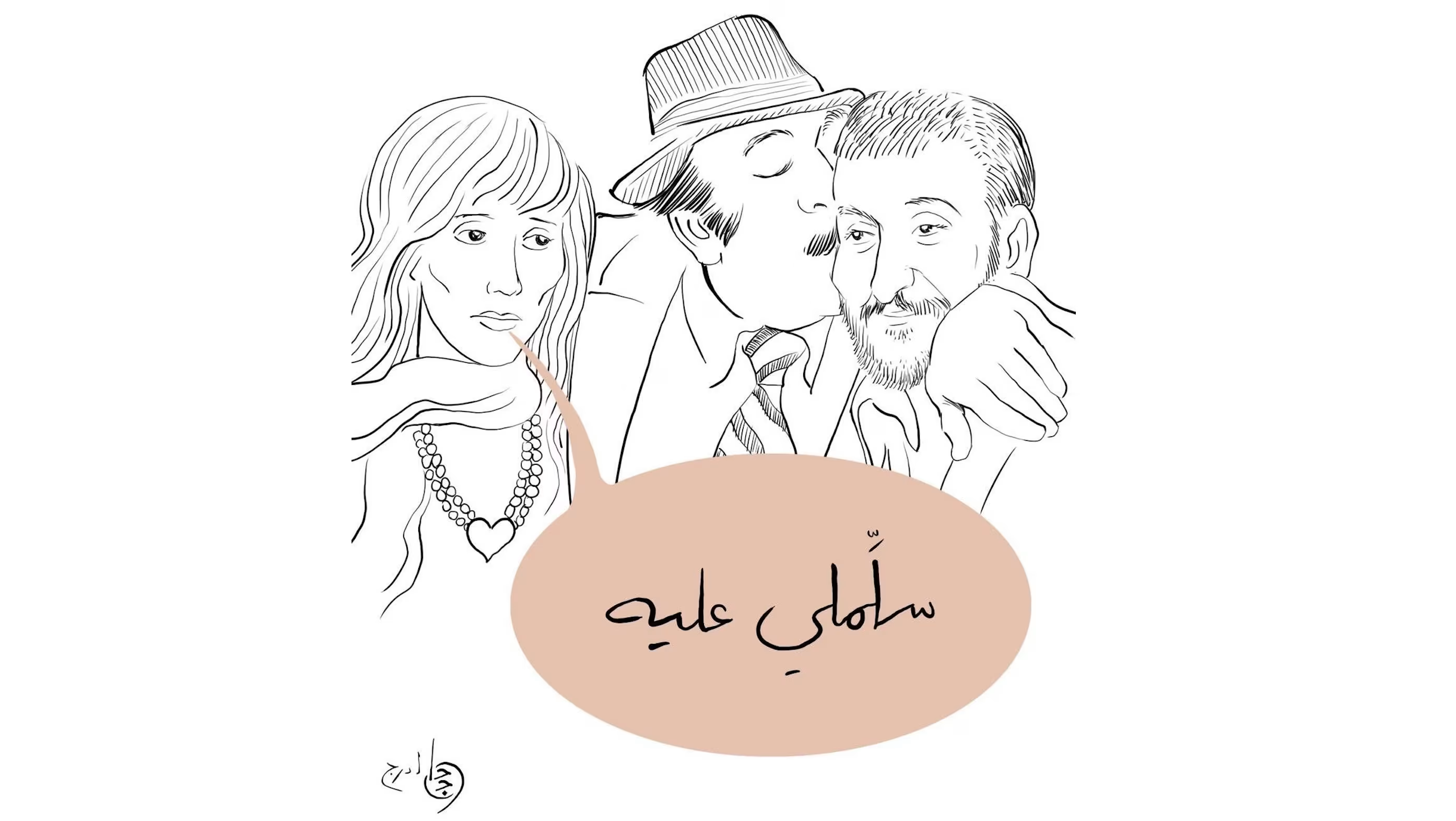

He was the son of artistic titans: the composer Assi Rahbani and the singer Fairouz, who together with his uncle Mansour, formed the legendary Rahbani Brothers. They created a Lebanon of the mind, a nation built of song. Their language was a beautifully curated Lebanese dialect, polished and poetic, evoking a timeless, idyllic village life. It was the language of pastoral romances under the cedars, of stoic mountain wisdom, of a national identity rooted in a pure, romanticized past.

This was not a falsehood; it was a form of national myth-making, a necessary art that gave a young country a sense of shared heritage. But as Lebanon spiraled into the chaos of the 1970s and the brutal Civil War, the chasm between that idealized language and the blood-soaked, cynical reality of the streets became impossible to cross.

He turned his back on the mythical village and tuned his ear to the city. He listened intently to the real-life symphony of Beirut: the slang of the militia fighters, the weary complaints of the shopkeepers, the code-switching of the bourgeoisie, the dark humor of the powerless. He picked up this raw, messy, living language—our language—and thrust it onto the stage and into the recording studio.

His plays really got audiences hyped up by breaking the fourth wall and showing them who they really were, frustrations and all, even with some cuss words thrown in. But what really blew me away were his song lyrics; he was a master at blending rhythm with everyday language. His lyrics pass as both non-sensical, and full of meaning at the same time, as all good song lyrics should be. As a wise man once said, meaning shouldn’t get in the way of what makes lyrics musically effective.

Through his unparalleled ability to blend poignancy, satire, truth, cynicism, and candidness, he addressed a myriad of topics. From the daily struggles of the working class to the absurdities of the bourgeoisie and the complexities of the female experience, his words resonated deeply. His profound and intricate relationships with women heavily influenced his plays and music, where scenarios and lyrics frequently portrayed the multifaceted problems within male-female relationships and offered a remarkably authentic and unfiltered portrayal of the Lebanese woman.

This man totally changed how we think about language and culture. In the Arab world, there's always been this big divide between fancy, Standard Arabic (Fus'ha) and the everyday spoken dialects. Fus'ha was for serious stuff—art, books, intellectual discussions. Dialects, though? That was just for talking at home or on the street, seen as common and not really fit for anything important. Ziad just knocked down that wall. With his lyrics, he proved that everyday language could do anything. He showed that the way a Beirut taxi driver talks could be used for deep thoughts about life.

His music really spoke to my generation and honestly, it really helped me connect with Arabic on a deeper level. That personal connection actually kicked off my work on Arabic language tools, something I've been super passionate about for years, and it eventually led to Aralects. I had always struggled with the language due to my schooling and a lack of immersion in my home country's culture, given the disconnect between it and what we encountered at the French school I went to. It was pretty rough dealing with that language discomfort right here at home.

Ziad Al Rahbani was a multifaceted artist for whom music—“the language of unspoken words”—became a dialect all his own, yet he avoided the trap that swallows many musicians: living so deeply in sound that ordinary speech fails. A philosopher as much as a composer, he carried even the most abstract ideas into crisp, everyday language, and it was precisely this dual fluency—melody and plain speech—that sharpened his satire and deepened his humanity. What can seem like shifts in tone were, in fact, the two registers he needed to tell the truth: blade-sharp disillusionment and overflowing empathy, together forming a mirror to a war-scarred Lebanon—once radiant, now frayed by sectarianism that gnaws at the fabric of a young nation, devouring its culture piece by piece.

كل حَياتي كِنِت عَلِّق أهَمِّيِة كْبيرة عَتاريخ صَلاحِيِّة كِل غَرَض بِشْتْريه. كْثير كان مْهِمّ هَالشي بِالنِسْبِة لإلي. مِن فَتْرَة بَطَّلْت... بَطَّلْت لأنُه لاحَظِت أنُه كِل شي عَم بِشْتْريه تاريخ صَلاحِيّْتُه... أبْعَد بِكْثير مِن تاريخ صَلاحِيّْتي أنا

زياد الرحباني

All my life, I used to obsess over the expiration date of everything I bought. It was always really important to me. But lately, I stopped… I stopped because I realized that everything I’m buying these days—its expiration date is way further out than mine.

Ziad Al Rahbani

A figure of profound debate, his melodies may stir dissent or delight, yet to disdain the man himself would be to deny a part of Lebanon's very soul and linguistic tradition. Ziad Al Rahbani, truly, was the living embodiment of a nation's spirit. And so it is, a collective whisper across the land, that his colossal influence, embraced or not, will forever etch his name among the titans.

We mourn not just the artist, but the mirror he held up to us, the voice that dared to speak our unspoken truths. Ziad Al Rahbani may be gone, but his legacy—the raw, honest, and profoundly human language he bequeathed to us—will continue to resonate in the streets of Beirut and in the hearts of a generation forever shaped by his defiant brilliance.

Thank you, and goodbye Ziad, you genius, you who decided to be a voice of truth. You who decided not to yield to being an echo of your lineage, and to pave the way for a Lebanon that does not submit, through thought, song, and language. You absolute legend. We will never see the likes of him again.