It was then—in those few months after graduating with a BA in Arabic and Linguistics, and before the outbreak of pandemic pandemonium—that I had my first, brief encounter with Iraqi Arabic.

Whilst getting acquainted with the language outside of the classroom and pencilled-over pages of

Al-Kitaab and ‘Arabiyyat al-NaasAl-Kitaab and ‘Arabiyyat al-Naastwo Arabic textbooks for beginning Arabic students

, I’d stumbled upon a video news report in which Iraqi citizens aired their frustrations about (unfortunately and unsurprisingly) corruption.

I, of course, relied on the Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) subtitles to understand the heart of matter.

Yet, I couldn’t help but focus on something else: that undeniably smooth melody of the Iraqi dialect, where each word blended seamlessly into the next, like lines of a poem I didn’t want to reach the end of.

Maybe it was just the romanticisations of a young linguist—but I was mesmerised.

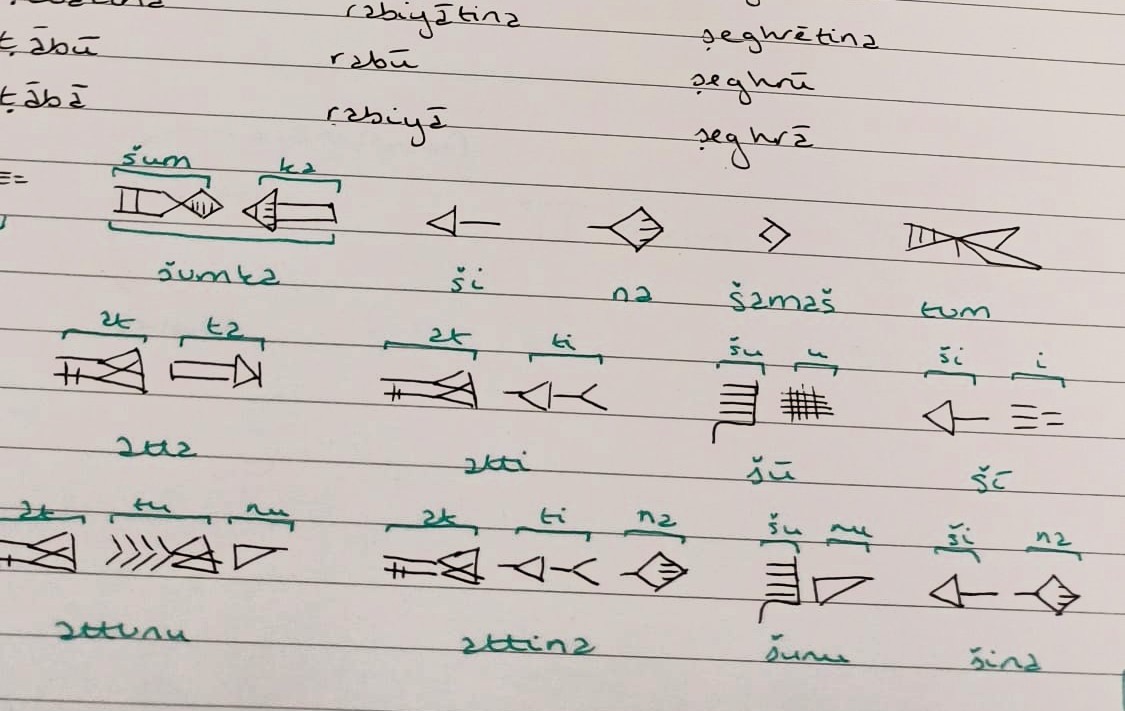

Fast forward to the summer of 2023 and there I was: studying Akkadian—an ancient East Semitic language that is closely related lexically and grammatically to its West Semitic cousin, Arabic. Akkadian refers to the two sibling varieties of Babylonian and Assyrian, both spoken in Ancient Mesopotamia (i.e. what is now modern-day Iraq).

Whilst Akkadian is older than Arabic, they have shared origins. So, it’s no surprise that we find core similarities in their vocabulary

Compare:

- atta and anta (أَنتَ) for “you”

- lišān and lisān (لِسان) for “tongue, language”

- šamā’ū > šamû and samā’ (سَماء) for “sky”

Nor can we be surprised that their grammar and morphology are so similar. Take case endings, for instance.

Somewhere between Ancient Mesopotamia and modern-day Iraq, I think I’ve gotten lost in thought…But, yes: my point is that even Classical Arabic (الفُصحى)—which some people portray as a “pure” and entirely unique language—was a product of a certain time, place, and particular influences. It arose from a kaleidoscopic linguistic landscape, and forms just a single branch of the deeply-rooted tree of Semitic languages.

And its modern form, MSA, is not inherently standard but, rather, standardised from a diverse group of language varieties.

Isn’t it interesting how we, as language enthusiasts, look at the Babylonian/Assyrian differences within Akkadian (e.g. bīt vs. bēt for “house”—c.f. the Arabic diphthonged bayt, بَيت) as the natural and enriching variations of any long-standing language fortunate enough to have lived on the tongues of a variety of speakers spread across varying geographical locations and time periods? So, why should we view Arabic’s varieties any differently?

My mind wanders back to the living language of that Iraqi Arabic clip, carrying in its melody the story and emotions of a certain people at that exact moment. And that’s really the crux of the matter, isn’t it? Because how can we listen to the story of a language if we won’t let it speak?